The Hitchhiker's Guide to Neural Networks - An Introduction

An introduction to neural networks for beginners.

Don't Panic!

If you’re one of those people who has been bitten by the bug of “Deep Learning” and wants to learn how to build the neural networks that power deep learning, you have come to the right place(probably?). In this article, I will try to teach you how to build a neural network and also, answer questions as to why we do what we do and why it all works. This will be a long in-depth article, so grab your popcorn, turn up your music and let’s get started.

Quick Tip: It would be more beneficial if you crank up your IDE and code along.

In simpler terms, neural networks (or Artificial Neural Networks) are computing systems that are loosely modeled after the biological neurons in our brains.

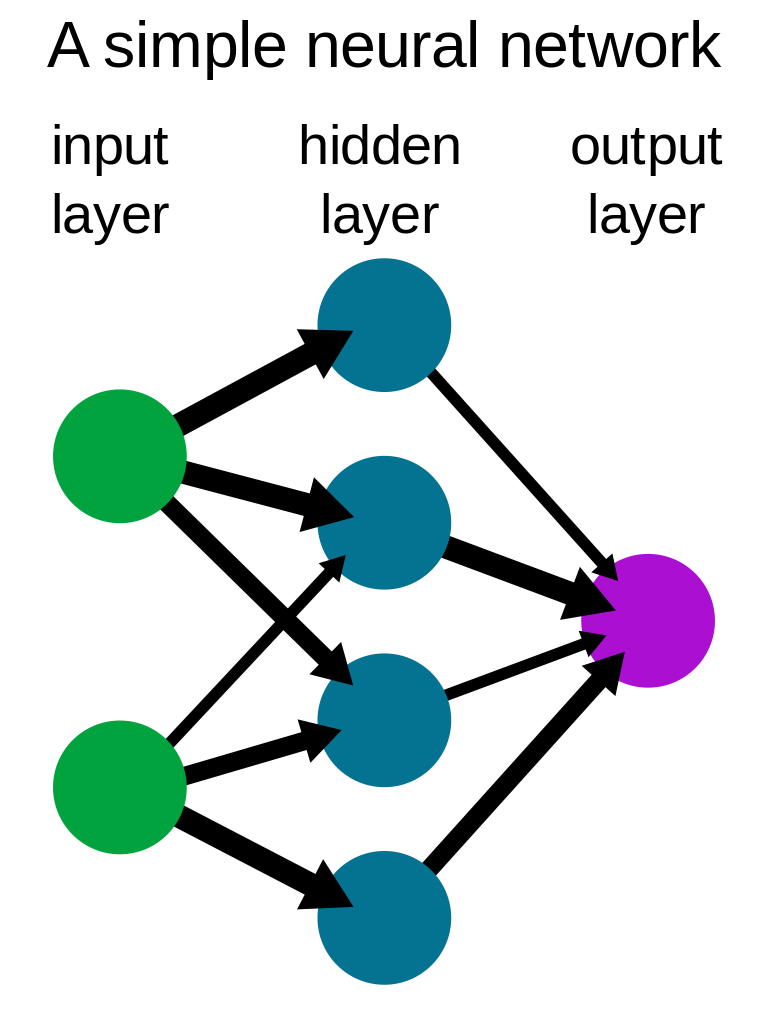

A neural network can be represented as a graph of multiple interconnected nodes where each connection can be fine-tuned to control how much impact a certain input has on the overall output.

Few points about a neural network:

- A single node in this network along with its input and output, may be referred to as a ‘Perceptron’.

- The network shown above is a 2-layer network because we do not count the input layer, by convention.

- The number of nodes in any layer can vary.

- The number of hidden layers can vary too. We can even create a network that has no hidden layers. Although one must keep in mind that just because we can, doesn’t mean we should.

- It’s vital to set up your neural network model perfectly before running it, otherwise you may end up imploding the entire Multiverse! Not really.

If it is still a bit unclear as to what a neural network is, it would only get clearer when we actually build one and see how it works. So, let me stop with the boring theory, and let’s dive into some code.

We will be using Python 3 and NumPy to build our neural network. We use Python 3 because it’s cool (read:popular and has a lot of superpowers in the form of packages and frameworks for machine learning). And NumPy is a scientific computing package for Python that makes it easier to implement a lot of Math (read:makes our lives a bit easier and simpler).

We will not be using the overly used and super boring “Housing Price Prediction” dataset for our tutorial. Instead, we will be using “Kaggle’s Titanic: Machine Learning from Disaster” dataset to predict who on the sinking Titanic would have survived.

Quick Tip: If you don’t know this already, Kaggle is a paradise for machine learners. It hosts machine learning competitions, tutorials and has thousands of funky datasets that you can use to do cool machine learning stuff. Do check it out!

What is our dataset?

The dataset consists of certain details about the passengers aboard the RMS Titanic as well as whether or not they survived. Before going further, I would recommend you clone the github repository (or simply download the files)from here.

Note: You can either type the code as we go. Or simply open the “first neural network.py” file that you just downloaded along with the dataset. I would recommend you type.

The train.csv file contains the following details( along with what they mean):

- PassengerId : A unique ID to identify each Passenger in our dataset

- Embarked : Port of Embarkation (C = Cherbourg; Q = Queenstown; S = Southampton)

- Pclass : Ticket Class

- Name : Name of the passenger

- Sex : Sex/Gender of the passenger

- Age : Age of the passenger

- SibSp : Number of siblings/spouses aboard the Titanic

- Parch : Number of parents/children aboard the Titanic

- Ticket : Ticket Number

- Fare : Passenger Fare

- Cabin : Cabin Number

- Survived : Whether or not they survived (0 = No; 1 = Yes)

The details numbered 1 through 11 are called the attributes or features of our dataset thus, forming the input of our model. The detail number 12 is called the output of our dataset. By convention, features are represented by X whereas the output is represented by Y.

Finally, take out your wand so we could conjure up our neural network. And if you’re a mere muggle like me, then your laptop will just do fine.

And now, let the coding begin.

import math

import os

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

The above code imports all the packages and dependencies that we will need. Pandas is a data analysis package for python and will help us in reading our data from the file. Matplotlib is a package for data visualization and will let us plot graphs.

def preprocess():

# Reading data from the CSV file

data = pd.read_csv(os.path.join(

os.path.dirname(

__file__), 'train.csv'),

header=0, delimiter=",", quoting=3)

#Converting data from Pandas DataFrame to Numpy Arrays

data_np = data.values[:, [0, 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 11]]

X = data_np[:, 1:]

Y = data_np[:, [0]]

# Converting string values into numeric values

for i in range(X.shape[0]):

if X[i][1] == 'male':

X[i][1] = 1

else:

X[i][1] = 2

if X[i][5] == 'C':

X[i][5] = 1

elif X[i][5] == 'Q':

X[i][5] = 2

else:

X[i][5] = 3

if math.isnan(X[i][2]):

X[i][2] = 0

else:

X[i][2] = int(X[i][2])

# Creating training and test sets

X_train = np.array(X[:624, :].T, dtype=np.float64)

X_train[2, :] = X_train[2, :]/max(X_train[2, :])#Normalizing Age

Y_train = np.array(Y[:624, :].T, dtype=np.float64)

X_test = np.array(X[624:891, :].T, dtype=np.float64)

X_test[2, :] = X_test[2, :]/max(X_test[2, :]) # Normalizing Age

Y_test = np.array(Y[624:891, :].T, dtype=np.float64)

return X_train, Y_train, X_test, Y_test

Phew! That’s a lot of code and we haven’t even started building our neural net. A lot of tutorials choose to skip this step and give you the data that can be easily used in our neural network model. But I feel that this is an extremely important step. And hence, I chose to include this preprocessing step into this tutorial. So what exactly is happening? Here’s what.

The function def preprocess() reads the data from the ‘train.csv’ file that we downloaded and creates a Pandas DataFrame, which is a data structure Pandas provides. (No need to worry too much about Pandas and DataFrames right now)

We take our data from the Pandas DataFrame and create a NumPy array. X is a NumPy array that contains our attributes and Y is a NumPy array that contains our outputs. Also, instead of using all the data from the file, we only use 6 attributes, namely(along with their changed representations):

- Pclass

- Sex : 1 for male; 2 for female

- Age

- Sibsp

- Parch

- Embarked : 1 for C; 2 for Q; 3 for S

We convert all the data of type string into float values. We represent string values with some numeric value. WHY? This is done because neural networks take only numeric values as inputs. We can’t use strings as inputs. That is the reason why all the data is converted into integer/float values.

Finally, we divide our data into training and test sets. The dataset contains a total of 891 examples. So we divide our data as:

- Training Set ~ 70% of data (624 examples)

- Test Set ~ 30% of data (267 examples)

X_train and Y_train contain the training input and training output respectively.

X_test and Y_test contain the test input and test output respectively.

The Test Sets contain whether or not the passenger survived.

Now, the question that you might be asking is, “What just happened? Why did we just divide our data into training and test sets? What is the need for this? What exactly are training and test sets? Why isn’t Pizza good for our health???”

To be completely honest, I really don’t know the answer to that last question. I’m sorry. But I can help you with the other questions.

Before we try to understand the need for different training and test sets, we need to understand what exactly does a neural network does?

A Neural Network finds (or tries to) the correlation between the inputs and the output.

So we train the network on a bunch of data, and the network finds the correlation between the input(attributes) and the output. But how do we know that the network will generalize well? How can we make sure that the network will be able to make predictions (correlate) new data that it has never seen before?

When you study for your Defence Against the Dark Arts exam at Hogwarts, how do they know that you actually understand the subject matter? Sure, you can answer the ten questions at the back of the chapter because you have studied those questions. But, can you answer new questions based on the same chapter? Can you answer the questions that you have never seen before, but are based on the same subject matter? How do they find that out? What do they do? They Test you. In your final exam.

In the same way, we use test set to check whether or not our network generalizes well. We train our network on the training set. And then, we test our network on the test data which is completely new to our network. This test data tells us how well our model generalizes.

The goal of the test set is to give you an unbiased estimate of the performance of your final network.

Generally, we use 70% of the total available data as the training data, and the rest 30% as the test data. This, of course, is not a strict rule and is changed according to the circumstances.

Note: Additionally, there is a “Hold Out Cross Validation Set” or “Development Set”. This set is used to check which model works best. Validation set (also called dev set) is an extremely important aspect and it’s creation/use is considered an important practice in Machine Learning. I omitted this from this tutorial for reasons only Lord Voldemort knows (Ok! I got a bit lazy). Now let’s move forward.

def weight_initialization(number_of_hidden_nodes):

# For the hidden layer

W1 = np.random.randn(number_of_hidden_nodes, 6)

# A [4x6] weight matrix

b1 = np.zeros([number_of_hidden_nodes, 1]) # A [4x1] bias matrix

# For the output layer

W2 = np.random.randn(1, number_of_hidden_nodes)

# A [1x4] weight matrix

b2 = np.zeros([1, 1]) # A [1x1] bias matrix

return W1, b1, W2, b2

The function def weight_initialization() initializes our weights and biases for the hidden layer and the output layer. W1 and W2 are the weights for the hidden layer and the output layer respectively. b1 and b2 are the biases for the hidden layer and the output layer respectively. W1, W2, b1, b2 are NumPy matrices. But, how do we know what the dimensions of these matrices will be?

Dimensions are as follows:

- W⁰ = (n⁰, n¹)

- b⁰ = (n⁰, 1)

where; 0 = Current Layer, 1 = Previous Layer, n = Number of nodes

Since, we are creating a 2-Layer neural network with 6 input nodes, 4 hidden nodes and 1 output node, we use the dimensions as shown in the code.

Why initialize the weights with random values, instead of initializing with zeros (like bias)?

We initialize the weights with random values in order to break symmetry. If we initialize all the weights with the same value (0 or 1), then the signal that will go into each node in the hidden layers will be similar. For example, if we initialize all our weights as 1, then each node gets a signal that is equal to the sum of all the inputs. If we initialize all the weights as 0, then all the nodes will get a signal of 0. Why does this happen? Because the neural network works on the following equation:

Y = W*X + b

But wait, what exactly is weight and bias?

Weight and bias can be looked upon as two knobs that we have access to. Quite like the volume button in our TV, weight and bias can be turned up or turned down. They can be used to control how much effect a certain input will have on the final output. There is an exact relationship between the weight and the error in our prediction, which can be derived mathematically. We won’t go into the math of it, but simply put, weight and bias let us control the impact of each input on the output and hence, let us reduce the total error in our network, thereby increasing the accuracy of the network.

Moving on.

def forward_propagation(W1, b1, W2, b2, X):

Z1 = np.dot(W1, X) + b1 # Analogous to Y = W*X + b

A1 = sigmoid(Z1)

Z2 = np.dot(W2, A1) + b2

A2 = sigmoid(Z2)

return A2, A1

The function def forward_propagation() defines the forward propagation step of our learning. So what’s happening here?

Z1 gives us the output of the dot product of weights with the inputs (and added bias). The sigmoid() activation function is then applied to these outputs, which gives us A1. This A1 acts as the input to the second layer(output layer) and same steps are repeated. The final output is stored in A2.

This is what forward propagation is. We propagate through the network and apply our mathematical magic to the inputs. We use our weights and biases to control the impact of each input on the final output.

But what is an activation function?

An activation function is used on the output of each node in order to introduce some non-linearity in our outputs. It is important to introduce non-linearity because without it, a neural network would just act as a single layer perceptron, no matter how many layers it has. There are several different types of activation functions like sigmoid, ReLu, tanh etc. Sigmoid function gives us the output between 0 and 1. This is useful for binary classification since we can get the probability of each output.

Once we have done the forward propagation step, it’s time to calculate by how much we missed the actual outputs i.e. the error/loss. Therefore, we compute the cost of the network, which is basically a mean of the loss/error for each training example.

def compute_cost(A2, Y):

cost = -(np.sum(np.multiply(

Y, np.log(A2)) + np.multiply(

1-Y, np.log(1-A2)))/Y.shape[1])

return cost

The def compute_cost() function calculates the cost of our network. Now remember, do not panic! That one line is loaded so take your time understanding what it is really doing. The formula for computing cost is:

cost = -1/m[summation(ylog(y’) + (1-y)log(1-y’))]

where; m=total number of output examples, y=actual output value, y’=predicted output value

Once we have computed the cost, we start with our dark magic of backpropagation and gradient descent.

def back_propagation_and_weight_updation(

A2, A1, X_train, W2, W1, b2, b1,

learning_rate=0.01):

dZ2 = A2 - Y_train

dW2 = np.dot(dZ2, A1.T)/X_train.shape[1]

db2 = np.sum(dZ2, axis=1, keepdims=True)/X_train.shape[1]

dZ1 = np.dot(W2.T, dZ2) * (1 - np.power(A1, 2))

dW1 = np.dot(dZ1, X_train.T)/X_train.shape[1]

db1 = np.sum(dZ1, axis=1, keepdims=True)/X_train.shape[1]

W1 = W1 - learning_rate * dW1

b1 = b1 - learning_rate * db1

W2 = W2 - learning_rate * dW2

b2 = b2 - learning_rate * db2

return W1, W2, b1, b2

The def back_propagation_and_weight_updation() function is our backpropagation and weight updation step. Well, duh.

So what is backpropagation?

Backpropagation step is used to find out how much each parameter affected the error. What was the contribution of each parameter in the total cost of our network. This step is the most Calculus-heavy step because we need to calculate the gradients of the final cost function with respect to the inner parameters(Weight and bias). For example, dW2 means the partial derivative(gradient) of the final cost function with respect to W2(which is the weights of output layer).

If this part seems scary, and you are as terrified of calculus as most people, don’t worry. Modern frameworks like Tensorflow, Pytorch etc. calculate these derivatives on their own.

So by backpropagation, we find out dW1, dW2, db1, db2 which tell us by how much we should change our weights and biases in order to reduce the error, thereby reducing the cost of our network. And so we update our weights and biases.

So what is Gradient Descent?

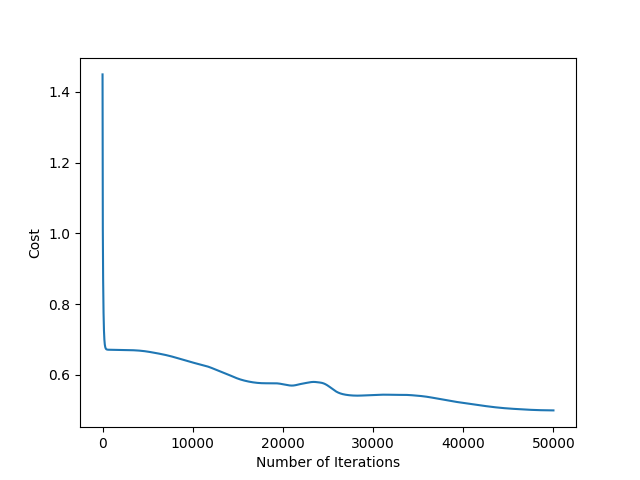

Iterating over the network again and again, we keep on reducing our cost of the network by going over the forward propagation and backpropagation step again and again. This iterative reduction of cost in order to find the minimum value for the cost function, is called Gradient Descent.

And what is learning_rate?

learning_rate is a hyperparameter that is used to control the speed and steps of gradient descent. We can tune this hyperparameter to make our gradient descent faster or slower in order to avoid mainly two problems:

- Overshooting : This means, we have jumped over the minima and are now stuck in a limbo. The value of cost function will go haywire and increase and decrease and do all sorts of things but won’t reach the global minima.

- Super long training time : The network takes so long to train that your body turns into a skeleton.

To prevent these two conditions from happening, we use the learning rate which is one of the many hyperparameters.

So that’s it, that’s all we have to do to train a network. After this, we use different evaluation metrics to test how good our network performs. And then, if we’re feeling fancy, we can use graphs to visualize what we have done.

So, tying all these function together, we write the final function.

if __name__ == "__main__":

# STEP 1: LOADING AND PREPROCESSING DATA

X_train, Y_train, X_test, Y_test = preprocess()

# STEP 2: INITIALIZING WEIGHTS AND BIASES

number_of_hidden_nodes = 4

W1, b1, W2, b2 = weight_initialization(

number_of_hidden_nodes)

# Setting the number of iterations for gradient descent

num_of_iterations = 50000

all_costs = []

for i in range(0, num_of_iterations):

# STEP 3: FORWARD PROPAGATION

A2, A1 = forward_propagation(W1, b1, W2, b2, X_train)

# STEP 4: COMPUTING COST

cost = compute_cost(A2, Y_train)

all_costs.append(cost)

# STEP 5: BACKPROPAGATION AND PARAMETER UPDATTION

W1, W2, b1, b2 = back_propagation_and_weight_updation(

A2, A1,X_train, W2, W1, b2, b1)

if i % 1000 == 0:

print("Cost after iteration "+str(i)+": "+str(cost))

# STEP 6: EVALUATION METRICS

# To Show accuracy of our training set

A2, _ = forward_propagation(W1, b1, W2, b2, X_train)

pred = (A2 > 0.5)

print('Accuracy for training set: %d' % float((

np.dot(Y_train, pred.T) + np.dot(

1-Y_train, 1-pred.T))/float(Y_train.size)*100) + '%')

# To show accuracy of our test set

A2, _ = forward_propagation(W1, b1, W2, b2, X_test)

pred = (A2 > 0.5)

print('Accuracy for test set: %d' % float((

np.dot(Y_test, pred.T) + np.dot(

1-Y_test, 1-pred.T))/float(Y_test.size)*100) + '%')

# STEP 7: VISUALIZING EVALUATION METRICS

# Plot graph for gradient descent

plt.plot(np.squeeze(all_costs))

plt.ylabel('Cost')

plt.xlabel('Number of Iterations')

plt.show()

We do 50,000 iterations of our training. num_of_iterations is also a hyperparameter. Once trained, we calculate the accuracy of our trained network on the training data. This comes out to be 79%.

Then we check how good our network is at generalizing by using our test data. This accuracy hits 81%.

The cost function decreases as shown in the following graph. Because graphs are cool!

As you can see, the cost of our network reduces drastically at first and then reduces slowly, before being plateaued.

Note: When you run this code on your machine, your graph might be a bit different because weights are initialized randomly. But still, you will get a nearly 80% accuracy on your training and test sets.

So, we are able to predict who would have survived the sinking of the RMS Titanic with an 81% accuracy. Not bad for a simple 2-layer model. Congratulations. You have built your very first neural network.

You’re a Wizard now!

Modern frameworks like Tensorflow and PyTorch do a lot of things for us and make it easier to build deep learning models. But it is important to understand what exactly is going on behind-the-scenes. I hope you found this article useful. And understand neural networks a bit better than you did before reading this article.

Do-it-Yourself: Try changing the hyperparameters(learning rate, number of iterations, and number of hidden nodes) to see how it affects the network. Also, try changing the activation function in A1 from sigmoid to tanh.

Now, how do we improve this network? How do we make this better? There are a lot of tips, tricks and techniques that can be used and you can learn about them at the University of Internet.